The Electric Tale of Pikachu - Toshihiro Ono's Pokemon is Both Opus and Onus, Offering Sophomoric Fun and Blunder to Teens and Tykes Alike

Ono's "loose" interpretation of the Pokemon Mythos sold millions in its day...only to never be released again. What happened?

One of the unlikeliest properties to penetrate the cultural zeitgeist—to become a phenomenon transcending all nations and borders—is Nintendo’s Pokemon, or “Pocket Monsters” as it was once known in its native land of Japan. It’s an inexplicable premise that could have only originated from a video game—with Game Boy in hand, players take the role of a ten-year-old kid scouring the land for the so-called monsters. Once a critter is found, players battle it with their own team of beasts, hoping to capture and thus add the creature to their ever-growing collection. In those early games, the goal was two-fold: Become the greatest “Pokemon trainer/champion” and, by extension, become a “Pokemon Master” by collecting every kind of poke-creature in existence. The original games—known to the West as Pokemon Red and Pokemon Blue—held 151 of these unique beasts. And catching them all was no easy feat.

Pokemon soon became an international sensation, proving popular enough to even extend the lifecycle of Nintendo’s already pitifully primitive Game Boy hardware. Indeed, the original games were quaint experiences, lacking the usual ingredients that made a JRPG (Japanese Role-Playing Game) “good.” Weak narrative, overly simplistic battle system, drab graphics and effects…Pokemon's redeeming features came more in its two-player, interactive features. By linking Game Boys, friends could battle their monsters in what amounted to being the cutest take on cock-fighting ever devised. The trading aspect proved even more enthralling; gamers could swap their monsters with other players via a Game Boy link cable, completing their collections not through digital roleplay and NPCs, but with real-life friends of flesh and consequence.

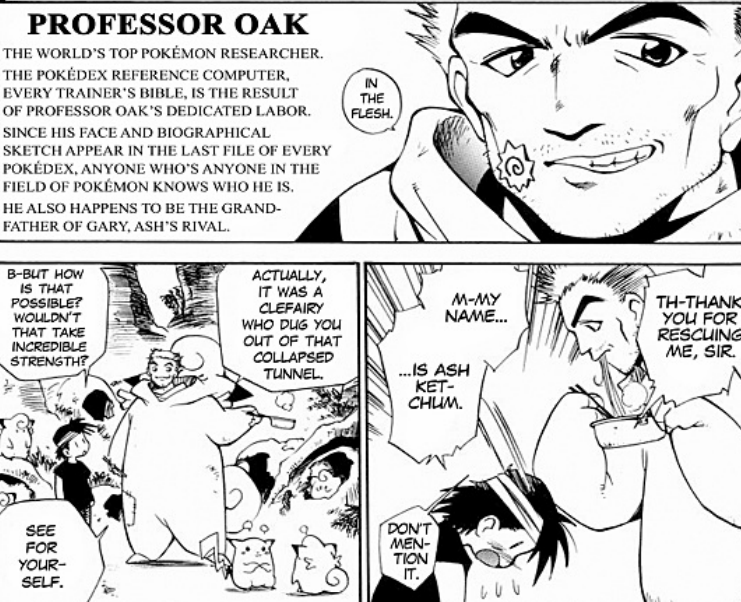

And yet, what really made Pokemon a true phenom came less from the games and more from their ancillary media. If the game’s main character “Red” seemed a bit too nondescript, his fights too static, his story too mundane, then television brought the cure with the Pokemon anime series in 1997. Red now became Ash Ketchum, a ten-year-old boy aspiring to be the world’s next Pokemon master. Far from being a boilerplate, flat protagonist, Ash was now dynamic and real—a boy as eager as he was immature, a kid as likable as he was over-confident, an underdog who must fail (again and again) before he prevails. Ash’s story was as much pratfall and panic as it was happy and heroic; his was not a hero’s journey, exactly, but more an extended stint of lessons and exercises in that pubescent circus of growing up, of becoming a man.

The anime, frankly, added in the flavor and antics the stodgy video game lacked, turning a 16X16 grayscale blip of a boy into a colorfully endearing and memorable hero—a character who became more like a brother to those who shared in his twenty-five seasons of hopes and disappointments. When people think of Pokemon today, more than any specific game, they think of him, Ash Ketchum. And, of course, his scene-stealing sidekick…the feisty Pikachu.

But the Pokemon experiment and expansion didn’t stop at the games, anime, and the endless supply of plastic merchandise. It also extended into manga, that huge and enduring market of Japanese comics. Since the late ‘90s, many a graphic novel has been written about those pocketable critters; some keep within the anime’s framework, providing alternate tellings of the game and anime’s storylines while others invent completely original tales. Many of these comics got translated for Western markets. And for various reasons, many of them didn’t.

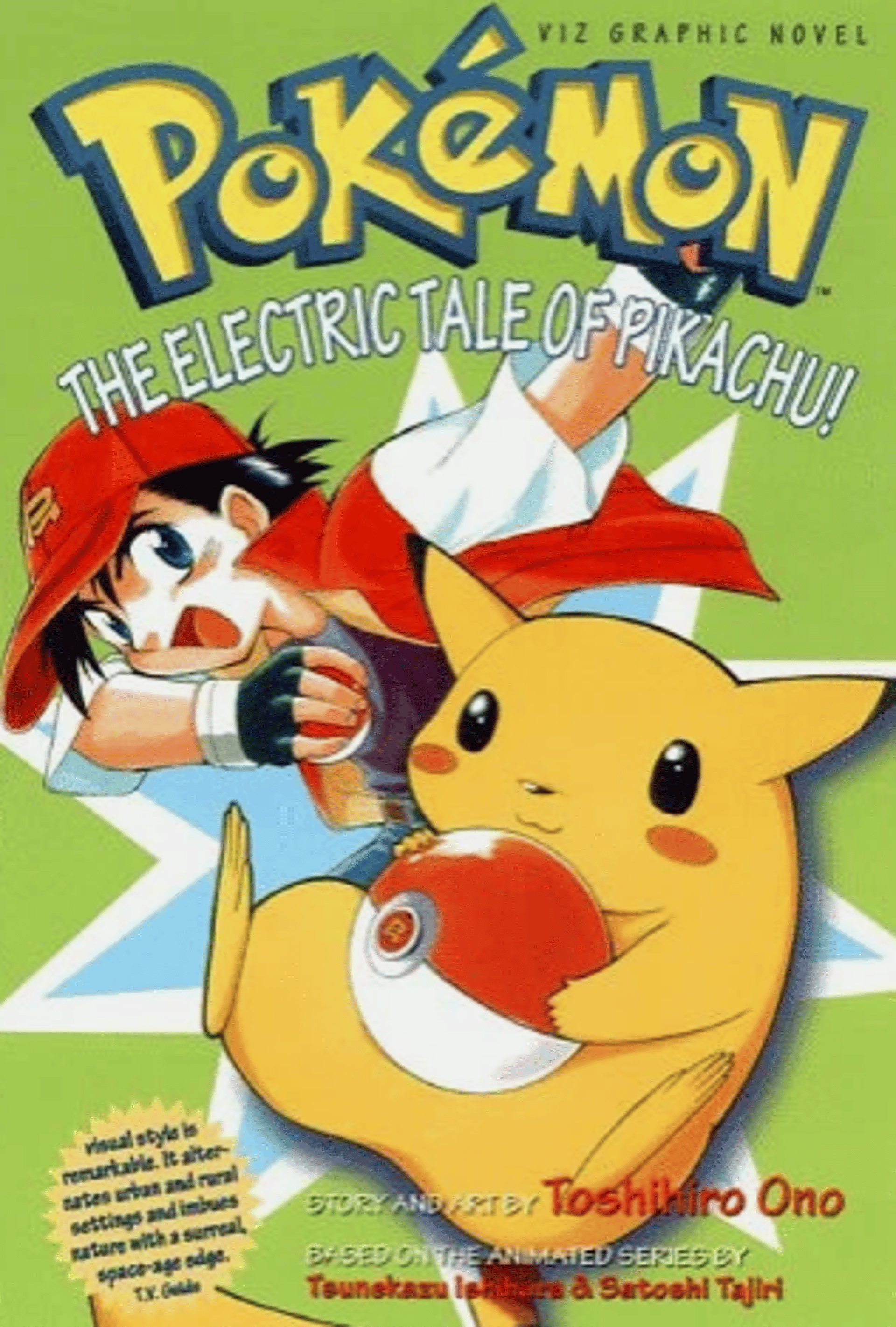

The Electric Tale of Pikachu—one of the earliest of these manga adaptations—did earn itself a Western release. It was widely popular. Sold millions of copies. Was even bragged about by its publisher, Viz Media.

And yet, years later, the series has been soundly and unapologetically buried, likely to never receive another release. And the reason is both shocking...and a bit ironic.

The Poke Phenom began with a humble Game Boy game. The gimmick was the double release--the blue version held monsters the red version didn't, and vice versa. To collect 'em all, players would then have to link their copy of the game with another's, trading for whichever critters they lacked.

Oh, the Irony

The ‘90s were a different time. Japan was a very different place, Nintendo an expressly different company. Moreover, the Pokemon franchise had yet to become a true, global enterprise. All of which explains why Nintendo, a game developer too busy to be bothered, was happy to license its property out to whoever tossed the funds without offering much in the way of guidelines or added oversight.

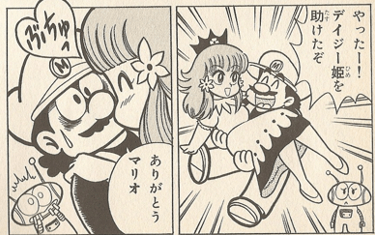

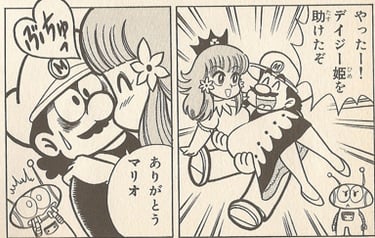

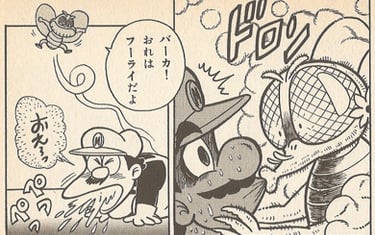

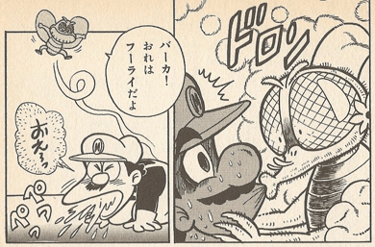

And why not? Nintendo’s properties had long suffered the quirky world of Japan’s manga fixation. Before Pokemon, it was Super Mario who received the bulk of the pulp, the plumber’s console and handheld adventures seen as easy vehicles for gags, slapstick, and that licensed cash. For the outsider, Mario might have seemed like Nintendo’s safe, noncontroversial mascot, but the icon's manga readership knew differently. More than a moral force, Mario was a farce—a clown inhabiting an absurdist world.

The original Pokemon games were rather, say, staid experiences. They required a helpful dose of imagination to really bring the titles' black and white, stodgy worlds to dynamic, flashy life.

The Pokemon anime provided the energy and flourish the Game Boy games lacked. Even today, the games can't quite capture the sheer excitement of the very best Pokemon episodes.

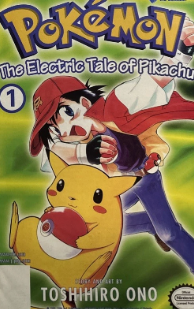

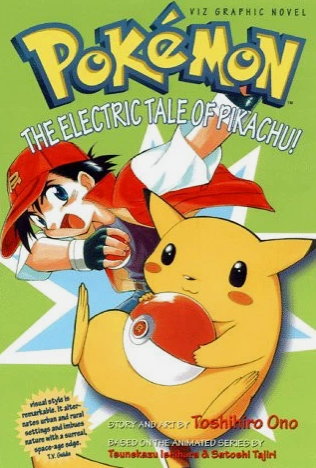

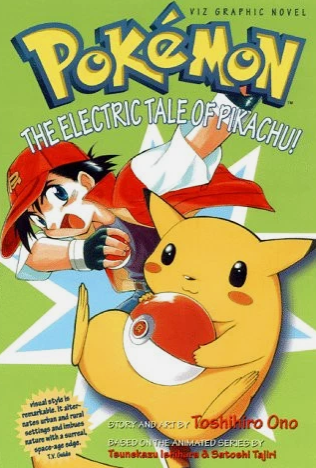

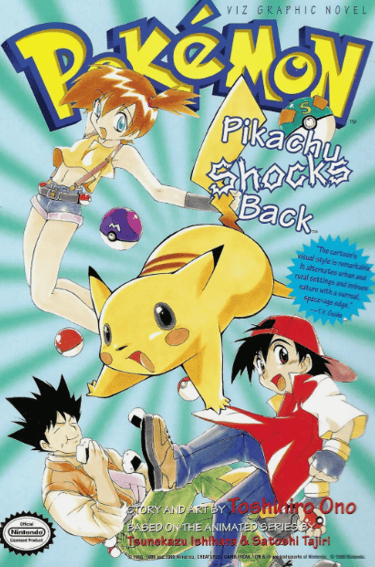

Viz Media released Pokemon: The Electric Tale of Pikachu as a four-issue series. Three more sets of four would follow before they all became collected in a four-volume series.

The first of Viz' four graphic novels.

It's hard to believe there was a time when Mario was more than just a sterilized corporate mascot. But, as these old comic samples show, years ago, Nintendo didn't mind creatives showing Mario picking his nose, being exposed, getting lip-locked with a bug, or even donning some hot fishnet stockings.

Modern Nintendo fans, or anyone caught in the West’s puritanical climes of A.D. 2025, will likely find the above pics a curious, even unfathomable puzzle. Why would Nintendo ever allow this? Wasn’t Mario, above all, meant for kids?

But again, 1990s-era Nintendo was a scrappier, less “corporate” company, and it saw no problem in allowing a talented mangaka turn Mario into the butt of some bizarre, even inappropriate joke. Mario, more than mascot, was a blank slate, so why not tuck a little ribald fun deep in the pages of some inconsequential comic? And Pokemon was no different; as this new property began to expand, Nintendo granted the manga scribes of the time a similar level of irreverent freedom. The property was still in its vaguest, earliest stages—was still more conceptual than truly commercial—which allotted artists all the outlandish latitude they needed.

Yet, nothing good ever remains; as Nintendo became a global powerhouse, it became more protective (and paranoid) of its company image and connective brands. From underdog to attack dog, the Big N began unloading a bevy of new corporate/censorious rules. Culture critics would say it was a necessary adjustment, but creatives would lament the sudden sterilization of artistic license and control. Nevertheless, in those waning, twilight days of the "old," less proper Nintendo, a certain work slipped through, one that would gain a kind of hated/celebrated notoriety. A Pokemon series that, at times, seemed to forget its intended audience—children. A Pokemon storyline that, sometimes, seemed blissfully unaware that its lead characters were kids themselves…not voluptuous high schoolers or jutty adults.

Welcome to the bold, bonkers, bodacious world of Toshihiro Ono’s Pokemon—a manga adaptation that wildly reimagines the early days of Ash Ketchum’s quest to be the best. Yes, the boy blunder still toils and struggles to collect them all, but amidst all the critters are a lot of topsy, hilly phillies—a lot of impressively developed, barely-adolescent tsunderes and femme fatales topped with enough unapologetic aplomb to make a Pokedex blush. Toshiro Ono’s take on the Pokemon saga was shameless and outrageous and, sometimes, unabashedly crass.

And yet, it was also excellent…instilling this revision of the mythos with a daring flair and creative quirk long lost to the mainline series.

The Electric Tale of Pikachu – Sixteen Comics, Four Unique Books

In American, Pokemon fever had grown into a wild fire, spreading across playgrounds and households alike. Pikachu was the new mascot of mass-market appeal, the games were sensations, and the anime was exploding, enthralling kids with an almost endless chronicle of Ash’s many (daily?) misadventures. The property’s profit potential seemed unstoppable, limited only by one’s lack of vision. In lieu of collectible cards, plushies, strategy guides, and the like, what else could generate some Pokemon-spawned cash?

Comics, naturally. And those of a specific Japanese-flavor. Viz Media, long known for being among the first to introduce manga to Western shores, was looking for another hit—or maybe, really, its bonafide first. Properties like Ranma ½ and Tenchi Muyo had their devotees, but hadn’t really penetrated the core comics market. So, just maybe, Pokemon would.

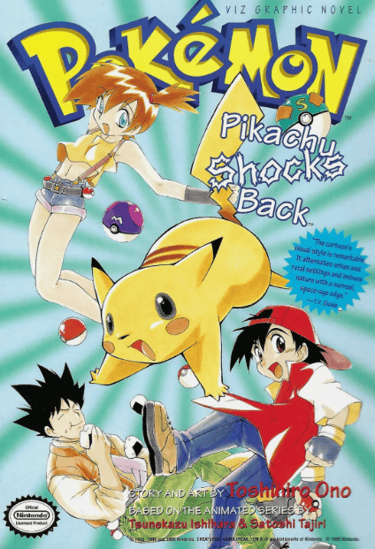

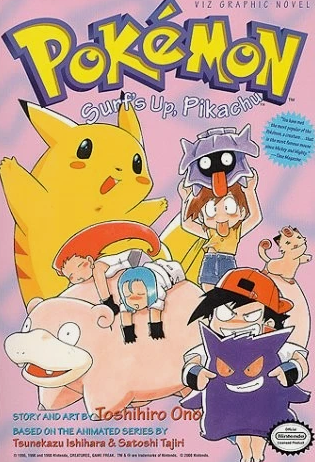

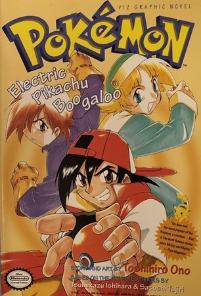

And thanks to a certain Toshihiro Ono, it actually did. The mangaka had already been working on a Pokemon serial for Bessatsu CoroCoro Comic Special, a children’s manga magazine. The stories were popular, the first chapters already done, and Viz Media was there to handle the localization and stateside release. Indeed, between November 1998 and February 2000, the publisher doled out Ono’s stories as sixteen individual, American-style comic books. And they sold in record-breaking numbers, with the first issue of The Electric Tale of Pikachu’s first issue selling over a million copies. Later, the stories would be collected evenly across four graphic novels: The Electric Tale of Pikachu, Pikachu Shocks Back, Electric Pikachu Boogaloo, and Surf’s Up, Pikachu. Similarly, these sold well.

Toshihiro Ono, the author and artist of what the West knows as Pokemon: The Electric Tale of Pikachu

Bessatsu CoroCoro Magazine is the home of many a manga-fied property, with even the Blue Blur himself getting adapted to its pages.

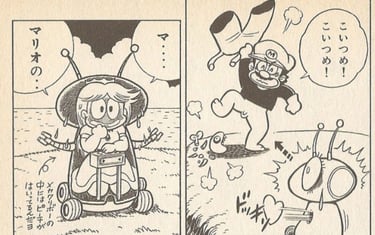

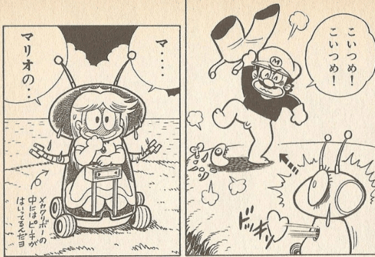

The Electric Tale of Pikachu continues informally in another three volumes. The last book, Surf's Up, Pikachu, offers a decisive finale featuring Ash competing at the Orange Island Championships.

Pokemon: A Pocket of Positives and Problems

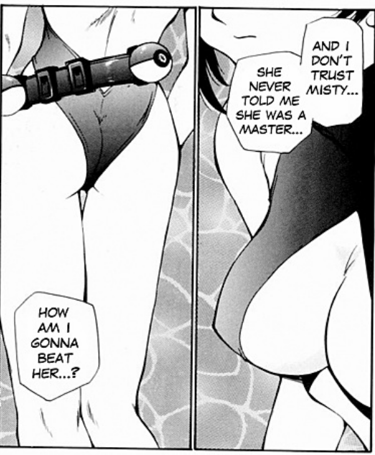

The entire sixteen-issue run was an undoubted success for Viz Media. But behind the scenes, there had been issues with those sixteen issues: Ono really liked to draw his girls a certain way, seemingly forgetting the predominately grade-school audience flipping through his pages. With no recourse, Viz was forced into clean-up duty, aiming to erase or “retailor” Ono’s wilder designs to make these children’s stories more appropriate for, well, children. But even with the publisher’s best camouflaging, the artist’s designs often defied the most careful efforts. Characters like the 12-year-old Misty could be redressed, but not exactly compressed...her tips and digits easily transcending that added ink.

Ono's opus is full of young girls writ large. Here, Ash's rival Gary has a very supportive sister. Somehow, "supportive" seems very fitting.

Here, Misty dresses for a Pokemon battle with Ash. Remember, she's (supposedly) only a twelve-year-old.

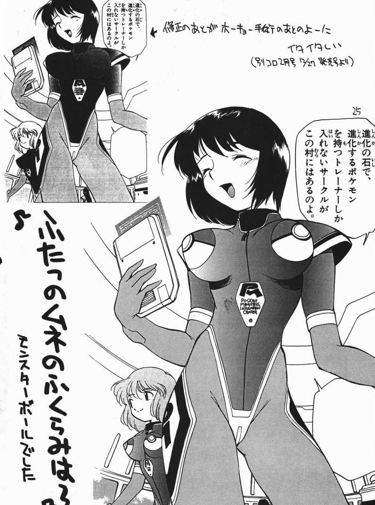

Examples of Viz's Western clean up job versus the Japanese originals. (Pics courtesy of Bulbapedia.)

Misty gets peeped by three amorous toms; the scene was so questionable, Viz simply excised it from the comic completely. (Pic shared by Bulbapedia.)

Clearly, even by Western standards, this was Pokemon of a different flavor, of a cheeky kink and sinking stink. Although Ash and Pikachu were still there, battling and struggling and pratfalling from one adventure to another, theirs was a world of an immature maturity, a land of innocent waifs oblivious to the grown-up cones they wielded so wantonly, so unironically. Such developments could/should have proven scandalous to its readership’s eyes, or, at least, that readership’s parents. But for better or worse, no one seemed to notice.

Indeed, whether due to parental ignorance or the more tolerant mores of the time, Viz never received much backlash for the underdressed Misty or any of its other strutty, jaunty ladies. If anything, Viz’s halfhearted edits were rewarded more than scolded with all those millions sold. Which begs a different question: If no one minded Ono’s exaggerated new take on the franchise—buying it in droves, in fact—why hasn’t the four-volume set ever been rereleased? Why the memory hole?

It's likely an inversion of the public's original indifference—what was merely iffy in 1999 has become rather icky in 2025. The West has become increasingly puritanical since those early aughts, judging anything too sensual—too feminine—as immediately suspicious. It’s a strange predicament that comes with its own conundrum: Is America more progressive now? Or was it more progressive then?

Nintendo, of course, is the other problem. In the ‘90s, the company didn’t care, even laughing at the idea of Mario exposed in the buff. Maybe even snickering at a Misty getting peeped in the bath. But that Small N died as the company grew to global prominence; like eating a super mushroom, Nintendo is the Big N now, with PR and profits its only mantra. This means The Electric Tale of Pikachu, once tolerated, once even beloved, has now been scrubbed by the perceived moral dictates of the current clime.

A Shame to Celebrate?

Toshihiro Ono, as most would agree, probably did overindulge with the sophomoric jokes and scenarios. But, maybe “sophomore” is the key word. If one could forget the franchise’s kiddie pretenses and, moreover, pretend Ono was writing for a more high school demographic using characters of a similar age, his vision for the Pokemon canon seems much less extreme. More flirty than dirty, perhaps. More cheeky than sleazy. If not exactly ennobling, when judged in an adjusted light, Ono’s opus at least deserves a partial redemption.

Truth is, The Electric Tale of Pikachu and its three succeeding volumes are a fine alternative to the mainline series. Everything is snappier and faster, more dynamic and intense. And yes, more mature—not just due to the girls’ boosted allure, but because, in this world, Pokemon are beasts that can really bleed. That can brutally die. This isn’t the video game or the TV show, but a strange and wonderful derangement thereof. Ono’s work, at its best, even grants the saga some needed dramatic heft and a philosophical edge largely absent from its sister forms. From Clefairy evolution rituals to a Haunter who would choose suicide over capture, Ono never forgot the truer plot. Pretty girls are nice, but in the end, those pocket monsters still own the show.

Which is to say, Ono’s opus probably deserves another chance—even if it means a “14+” maturity label smacked upon a tightly-sealed 4-volume set. But until Nintendo and a willing publisher are ready to ignore the purity police and give this series a second release, the mangaka's sixteen tales remain lost to that purgatory of late ‘90s life. A time in which Nintendo and a little innuendo wasn’t so bad…so long as the stories themselves were good.

Toshihiro Ono’s Pokemon is a tale of irony, a storyline that sold millions before being eventually condemned. But, in fairness to the artist, he was commissioned to do exactly what he did: to reinterpret and improvise, to engage and entertain. Ono’s more suggestive jokes were clearly for the older folks—those who would appreciate his more satiric upturning of the Pokemon world. If ten-year-old boys can roam dangerous lands like the most macho of men, why can’t the girls brandish themselves like the womanliest of women?

And that’s the choice modern readers have. Either scream at the trash…or take the wink and have a good laugh.--D

As Nintendo "evolved," its Mario had to become safer, softer, and more generic. He had to be neutered, in a sense.

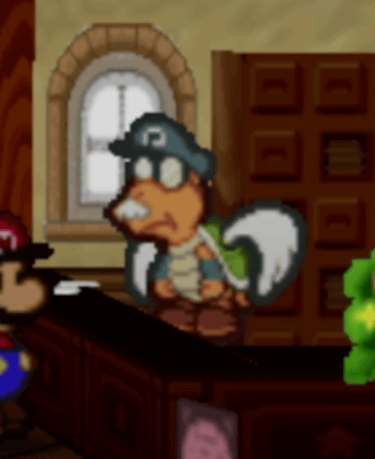

Nintendo's homogenization of its properties eventually reached beyond the core mascots. The creative freedom seen in Paper Mario's character designs, for instance, was soon forbidden across all media in favor of more "conventional" renditions.

Controversial art aside, there's no denying the quality of Ono's work. His stories are creative and mature in a way that usually eludes the property's other forms. Note Ash's blood trickling onto Pikachu in the bottom-most shot. If not always mature, the series can certainly be dramatic.

Contact: lostnostalgiaproductions@gmail.com

Website: www.lostnostalgia.com

Like what we're doing? Please consider throwing us a dollar into our Patreon page's tip jar!